Regarding presentation, the Karagoz puppet theatre stage is separated from the audience by a frame holding a sheet of any white translucent material but preferably fine Egyptian cotton. It is mounted like a painters canvas, stretched taut on a frame. The size of the screen in the past was 2 m x 2.5 m; in more recent times it was reduced to 1 m x 1.60 m. The operator stands behind the screen, holding the puppets against it and using an olive-oil lamp as a light source from behind. An oil lamp is preferable as it throws a good shadow and makes the characters flicker, this giving them a more lifelike appearance. The light is fixed behind and just below the screen. The light distance is determined by the need and curtain on which the shadow is to be thrown. The screen diffuses the light, and the light shines through the multicoloured transparent material, making the figures look like stained glass. The puppeteer holds the puppet close against the screen with rods held horizontally and stretched at right angles from the puppet. With horizontal rods held at right angles to the screen there is far less shadow on the screen, but control is limited. The Turkish puppets are worked by horizontal rods, unlike the Javanese and other Southeastern shadow puppets which are moved and supported by vertical rods. However, there are two devices which provide alternatives to the usual horizontal rods employed in Turkish shadow show. One is hayal agaci -puppet-tree-. The operator can manipulate only two figures at a time; so when there is a demand for more than two figures on stage, he uses this device. The puppet-tree is a Y-shaped rod. Y-shaped rods are stuck into the holes on the ledge at the bottom of the screen so that they stand vertically. The horizontal rods of the figures are placed in the cleft of these rods, so that when the puppeteer presses the ends of the horizontal rods against the screen with his chest or stomach, these figures stand still and do not move. Through this device a crowd scene can be easily accomplished. The second device is called by the shadow puppeteer firdondu, a -swivel-, which is designed to overcome a disadvantage presented by the horizontal rods- that is, the puppets can not be turned round to face the other way. This device is similar to that used in the Chinese shadow play. It is simply a rod wire fixed in a wooden handle, the curved end of which is inserted in small leather socket on the outer edge and at the back, in a sort of hinge attached to the figure. The puppeteer can give it a quick flip in order to make the figure face in the opposite direction. There are a few Turkish shadow puppet theatre figures fitted with this device in the Hamburg and Topkapi Palace collections, showing that it has been known by the Turks for some time. Puppets are operated on the plane of action and the length of the control rods can be adjusted to the socket of the puppets, allowing the puppets to work in the upper areas without the shadow of the operator’s hands being visible. Along the bottom edge at the back of the screen is a batten to act as a rest for the legs of puppets. Underneath this there is a horizontal ledge to put the oil lamps on. This ledge also has some holes on its surface to stick the supporting rods, the puppet-trees.

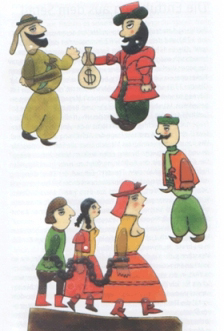

The figures are flat, clean-cut silhouettes in colour. Animal skin is used in the making of the puppets, especially that of the camel. The skin is well rubbed and soaked in a solution containing bran to remove its oil properties and to make it softer. The skin is dried under the sun during the months of July and August. It is smoothed out and treated until it is almost transparent, and it is well scraped with a piece of broken glass to remove hairs. Finally it is rubbed and polished. The outline is drawn by applying a mould or a pattern and the lines cut out with a small curved knife called nevregan. The cut-out is then stained with translucent vegetable dyes of tender blue, deep purple, leaf green, olive green, red crimson, terracotta, brown and yellow. Jointing is done with a piece of gut threaded through each of the two pieces at the point of overlap and then knotted on both sides. The action of the figures dictates their shapes. Each of them has a hole somewhere in the upper part of the body, which is reinforced by a double leather piece like a socket into which the control rod may be snugly inserted from either side. A second rod gives Karagoz his distinctive action. A good number of Turkish puppets have an articulation between head and body, which is usually the only articulation, the rest of the body below the neck being in one piece. In such puppets, the manipulation-rod hole is in the neck. In this way a figure can do a complete somersault with a twist of the rod. Apart from this, Karagoz,s arm is made up of two joints, and his headgear is attached by a loose joint at the back of the head; so with a quick flick of the puppeteers wrist, the headgear can fall back to expose Karagoz,s bald head. Karagoz is not the only figure that is manipulated by two rods. The socket of the rod is carefully placed so that the puppet will balance properly. Figures can thus make sweeping bows to the ground or incline their bodies backward to gaze at the sky.

The achieve magical transformation, the shadow puppet theatre uses various devices. For instance, there is a puppet with two heads, one of which is concealed behind the body. When the action calls for a figure’s head to change into a donkey’s head, by turning the rod in one complete revelation, the concealed donkey,s head takes the place of the actual head, which in turn is hidden behind the body. However, in order to change a character’s costume or strip, two separate representations of the same figure are used. Puppets range in size from 24 centimeters to over 35 centimeters in height. An average size is about 30 centimeters (12 inches). The smallest figure is a dwarf, approximately 20 centimeters in height, while the tallest is Baba Himmet, a little over 57 centimeters

*Drama at the Crossroads, By Metin And

Emin Senyer is making a puppet